This Saturday marks the 75th anniversary of the surrender of Japan which ended World War Two.

VJ Day celebrations may have largely been cancelled, two 99-year-old veterans from Holbeach will be among those holding their commemorations of events.

Both Alan Barkes and Jack Mills were readying themselves for incredibly dangerous missions when the news the war was over broke on August 15, 1945.

Leading aircraftsman, Barkes of the 2810 Parachute Squadron, was on board the plane about to set off for Operation Zipper, the invasion of Singapore.

“Someone came to us at around 10.30am and said to us ‘right lads, this is it’ and we all got on the Dakota on the runway.

“Then as we were on the plane, someone told us the war was all over.”

When asked how he felt both then and now he says:

“Oh dear. I don’t think I would have been in Holbeach like I am now if it hadn’t have happened then.

“We then flew to to Singapore and after we’d got there we helped round the Japanese up.

“We hadn’t been there 20 minutes when two Japanese officers marched up to us.

“I got the sergeant and he bowed to me.

“It’s a moment I shall never forget.”

Jack does not remember too many celebrations of the news the war was over as his small RAF Mobile wing readied itself for the invasion of Malaysia.

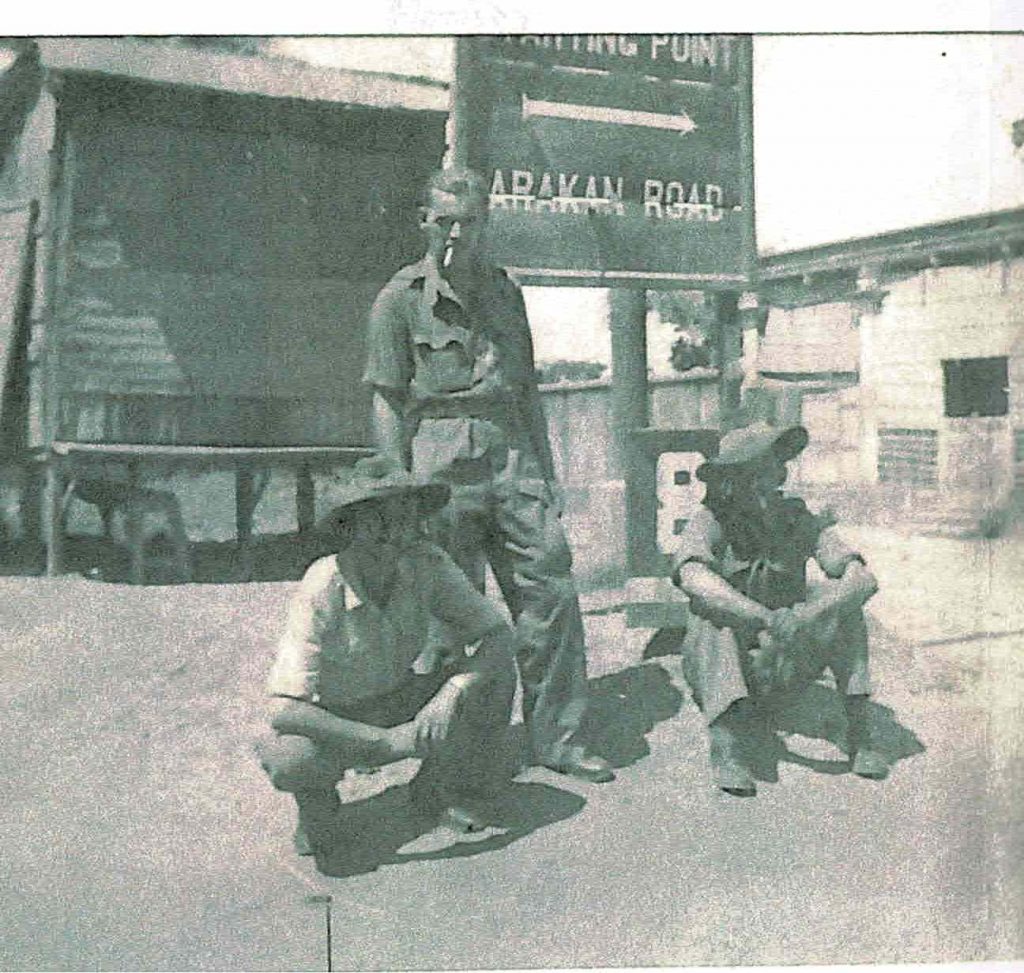

He was in the most forward unit in Burma (now Myanmar) loading Dakotas.

He said: “We were on Runway Island packing our bags ready for the invasion of Japan when the news filtered.

“There wasn’t any big announcements or anything like that.

“The news just filtered through and we were set to return. There were no great celebrations.”

Jack’s memories – “On board a troopship to Bombay and across India by trooptrain to the Bay of Bengal, I was kitted out with tropical gear including a Sten machine gun, steel helmet and gas mask.

“My small RAF unit was picked up by a supply dropping Dakota aircraft with some well-used tents and flown into a landing strip in the jungle

“The hurriedly constructed landing strip was of earth covered with hessian soaked in tar and covered in Mecanno type metal sheeting.

“Dumped alongside the metal track and our tents elsewhere, with nowhere to go, we spent the night sleeping on the side of the track with a tarpaulin sheet over us.

“We had a cook in our unit and he rigged up a 44 gallon oil drum with a wood fire and we queued up with our enamel mugs and billy cans.

“The noise in the jungle at nights, the howls of the jackals, the babble of the monkeys in the trees, the croak of the bull frogs during the monsoon.

“But it was the noiseless ones to be feared, such as the mosquitos, snakes of all sizes.

“You had to be on your guard against the Japanese who roamed the jungle in small parties like wild animals. The landing strip with trees and elephant grass 10 feet high had no defences.

“The strip was used by Dakotas dropping supplies to the troops on the front and the army Chindits operating in the jungle behind the Japanese forces.

“Our unit was the most forward unit of its kind in Burma and being a mobile unit to other landing strips as the fighting moved south.

“Life was primitive. We had a few stable lanterns for loading the Dakotas at night ready to take off at first light.

“We never saw a woman. Water was scarce and the food was either powdered or dehydrated with tins of bully beef.

“We never saw an egg or bread and tea was jam on dogs’ biscuits.

“We survived.

“The Dakotas were flying trucks with bare fuselage and a large hole in the side for dropping supplies flown by young pilots in their early 20s who possibly had never driven a car.

“They saved the lives of the troops on the front line and in turn they saved our lives from the Japanese onslaught.”